Lesson 1: How Technology Platform Shifts Reshape the World

Technology platform shifts, their impact and how you can benefit from once in a generation economic and technological changes.

Every decade or so, we see the emergence of a new technology that changes how we develop tools, solve problems, and organize ourselves. Generative AI is just one such technology shift people have lived through, and one of many we are currently living through. We will cover what historically happens in a technology shift and the impact we can expect to see in the tech industry and beyond.

Find all the lessons in The Economics of AI here.

The Golden Age’s mission is to build a more peaceful and prosperous world by popularizing and applying first-principles thinking to the problems around us. Join our community of first-principles thinkers, builders, and investors.

Technology platform shifts

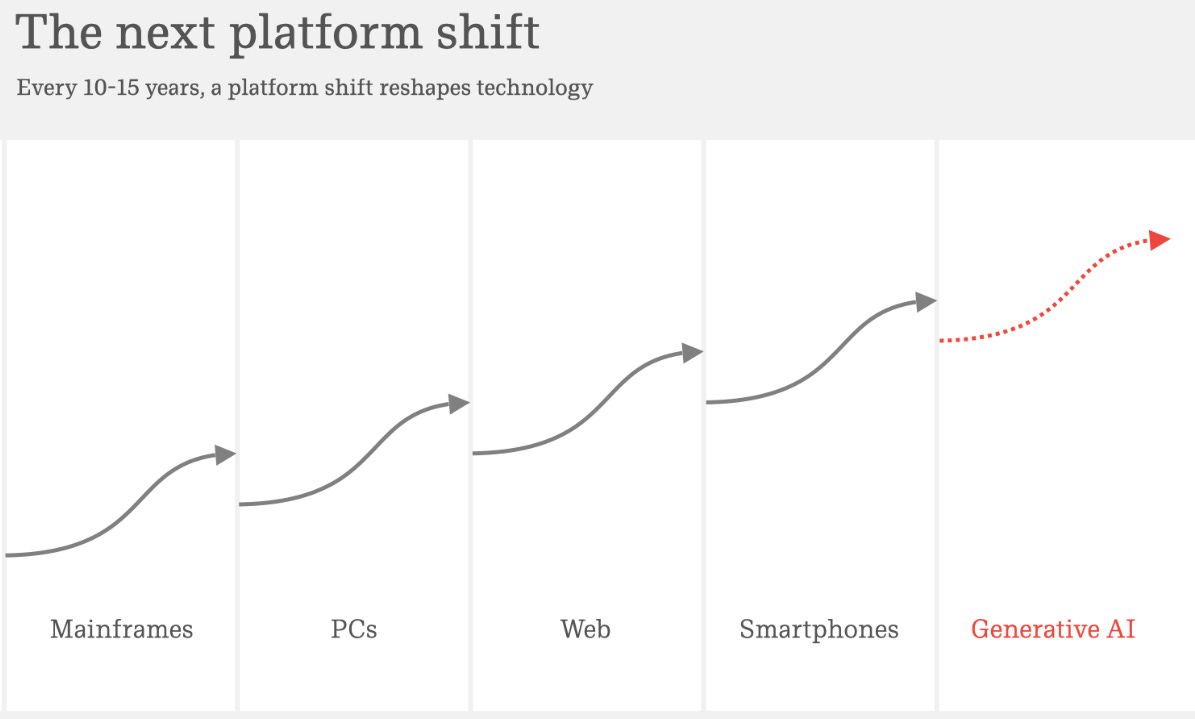

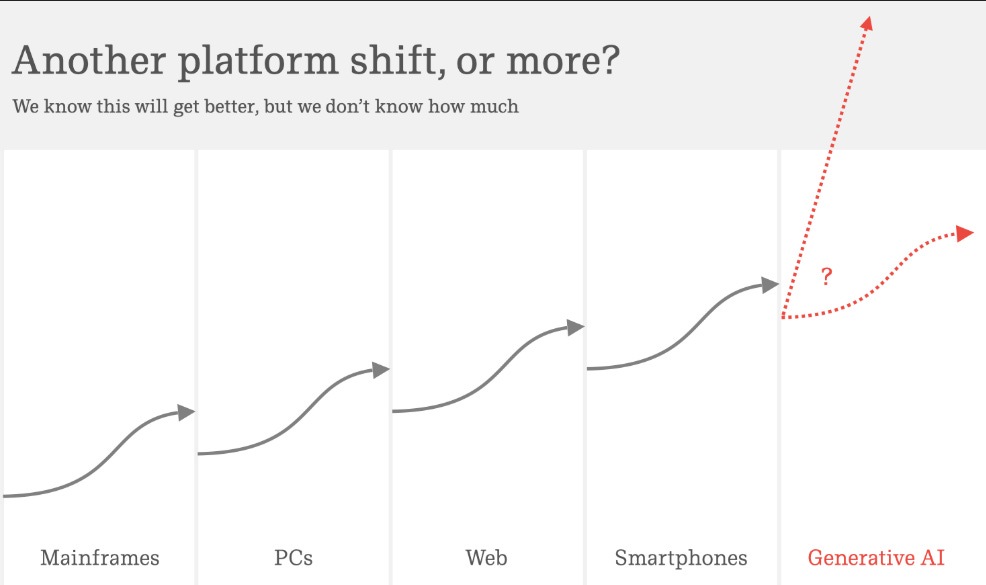

If we think about the progression of technology over the last 50 or 60 years we've tended to move in cycles, so we have a platform shift every 10 or 15 years. We had mainframes and then we had PCs and then the web and then smartphones and you could put other things on here. You could put databases or client server or open source. And each of these pulled in all of the investment and innovation and company creation. The old thing is still there. Airlines still run on mainframes, banks still run on mainframes, but the new thing is where all the innovation, all the investment, all the change, all the company creation happens. And so the view is that now this is the next platform shift. Generative AI is the next thing after smartphones, after the web, after PCs.1

Although we will focus on Generative AI this time, let us not forget that we are going through multiple technological platform shifts: robotics continue to revolutionize warfare, manufacturing, and healthcare; machine learning and computer vision is revolutionizing transportation; new technologies in rocket science will open up the final frontier of space exploration and allow everything from tourism to drug development and manufacturing in microgravity.

The tech industry moves in platform shifts, and Generative AI is a new platform shift.

We want to focus on three questions about technology platform shifts to understand not only Generative AI but all innovations, technology or otherwise, that will be developed in the future and change the way we live:

What happens in a platform shift?

What lessons have we learned from the previous platform shifts?

What should we expect from the current platform shift of Generative AI?

What happens in a platform shift?

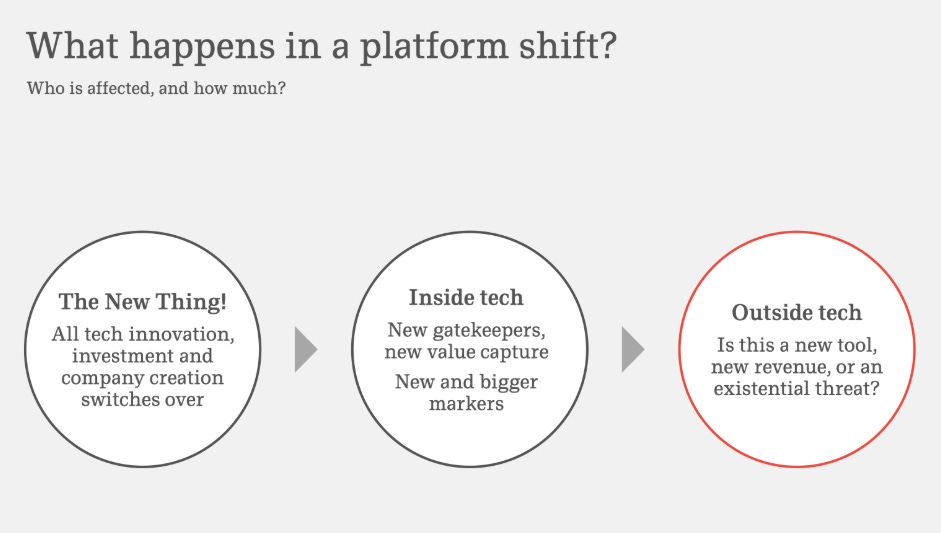

All the technology innovation, investment, and company creation moves to the new thing.

Meta is a perfect example of it. Remember when smartphones became the main thing, and Mark Zuckerberg pivoted the entire company to mobile, only to pivot again when Augmented and Virtual Reality became the new hot things? Meta reportedly spent ~$50B on developing its metaverse and AR/VR products, and in the process, booked ~$45B in operating losses, per its own disclosures. Only now to pivot their focus again to LLMs and Generative AI.

When mobile became the new technology platform, practically every start-up was trying to build for mobile; that is how we got Uber and Uber-like services, Social media applications, and millions of other mobile-first applications we can’t live without.

Across the economy, a few things happen:

All of the technology innovation and

the investment (think Meta shifting focused to applications for smartphones, then building out the Meta-verse), and

company creation (startups, think new smartphone apps like Uber, Instagram, and now OpenAI, Grok etc) moves to the new thing2

Secondly, inside the tech industry, a few things happen:

new gatekeepers emerge,

old gatekeepers fall,

new value capture emerges,

new and bigger markets appear, and

old things get destroyed.

A note on value capture

New value capture refers to how value and profits shift to different parts of the ecosystem during a platform shift. In every major technology transition, the way companies make money and who captures the most value changes dramatically.

Examples from past platform shifts:

PC era: Value shifted from hardware manufacturers to software companies (Microsoft, Adobe) and microprocessor makers (Intel)

Internet era: Value moved from traditional media and retail to online platforms (Google, Amazon, eBay)

Mobile era: Apple and Google captured massive value through app store ecosystems, taking 30% cuts from developers

Cloud era: Value shifted from on-premise software licenses to subscription models (AWS, Azure, SaaS companies)

In the Generative AI shift, new value capture means we’re seeing:

Foundation model companies (OpenAI, Anthropic) are capturing value through API access

Cloud providers capturing compute costs

New application layers are being built on top of AI models

Uncertainty about where sustainable margins will settle - will it be the model layer, the application layer, or somewhere else entirely?

The key question is: who will capture the economic value in this new platform? Will it be the infrastructure providers, the model builders, the application developers, or the end-user-facing companies?

Thirdly, outside the tech industry, everyone is trying to figure out what to do with the new technology. Everyone is trying to answer:

Is this a new tool?

Is this a new feature?

Is this an existential threat?

How much do we have to care about it?

That’s what every big company is thinking about the Generative AI right now.

Dominance is won and lost

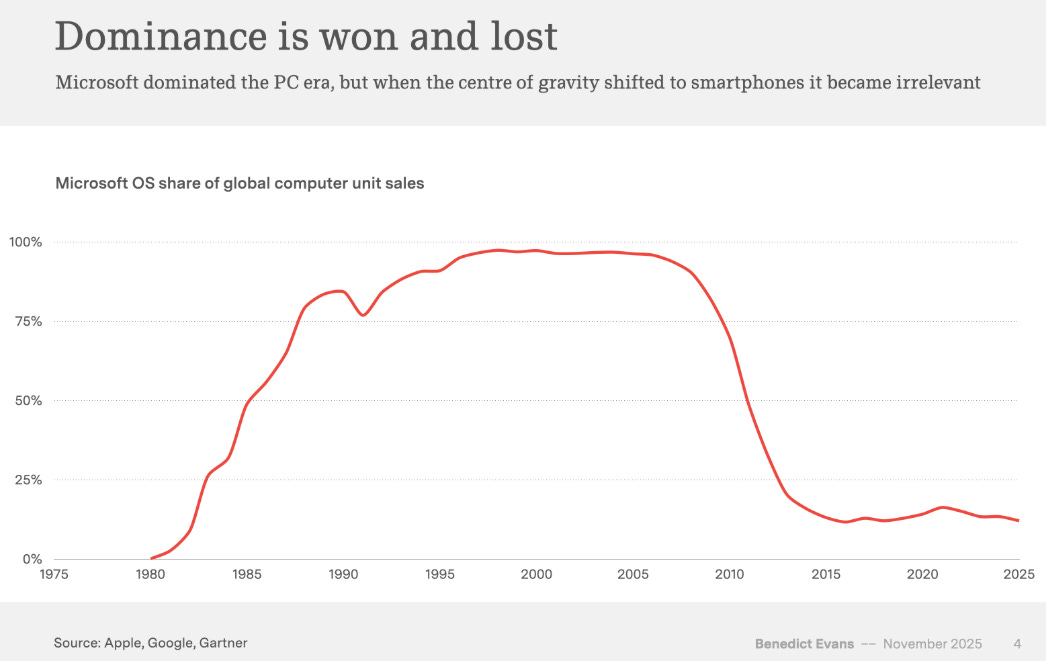

Inside technology industry, platform shifts mean that companies gain dominance and lose dominance.

This is Microsoft's share of computing. When the PC was the center of the tech industry, that was Microsoft. They dominated it. When we moved to smartphones, Microsoft became irrelevant for a decade because they were no longer a player in the thing that set the agenda.

The Microsoft graph shows the percentage market share of operating systems across all devices, including smartphones. Microsoft failed at developing an operating system for the next generation of computers - smartphones - and paid the price by losing market value for a straight 17 years. It is very costly for technology companies to miss a technology platform shift, as we will see from quotes of prominent technologists below. Also, this is the primary reason Warren Buffett stayed away from investing in technology companies: they are one innovation away from bankruptcy.

It is very costly for technology companies to miss a technology platform shift, as they are one innovation away from bankruptcy.

For this next Generative AI platform shift, think about business models that are being impacted and are not adopting, like Blockbuster when Netflix launched unlimited streaming. For example, content mills, agencies producing high-volume, low-quality blog posts, SEO articles, and filler content at $0.01–$0.10/word have been entirely replaced by Generative AI. Low-effort / low-value work is the first to be automated, as we will discuss in future posts.

Low-effort / low-value work is the first to be automated, as we will discuss in future posts.

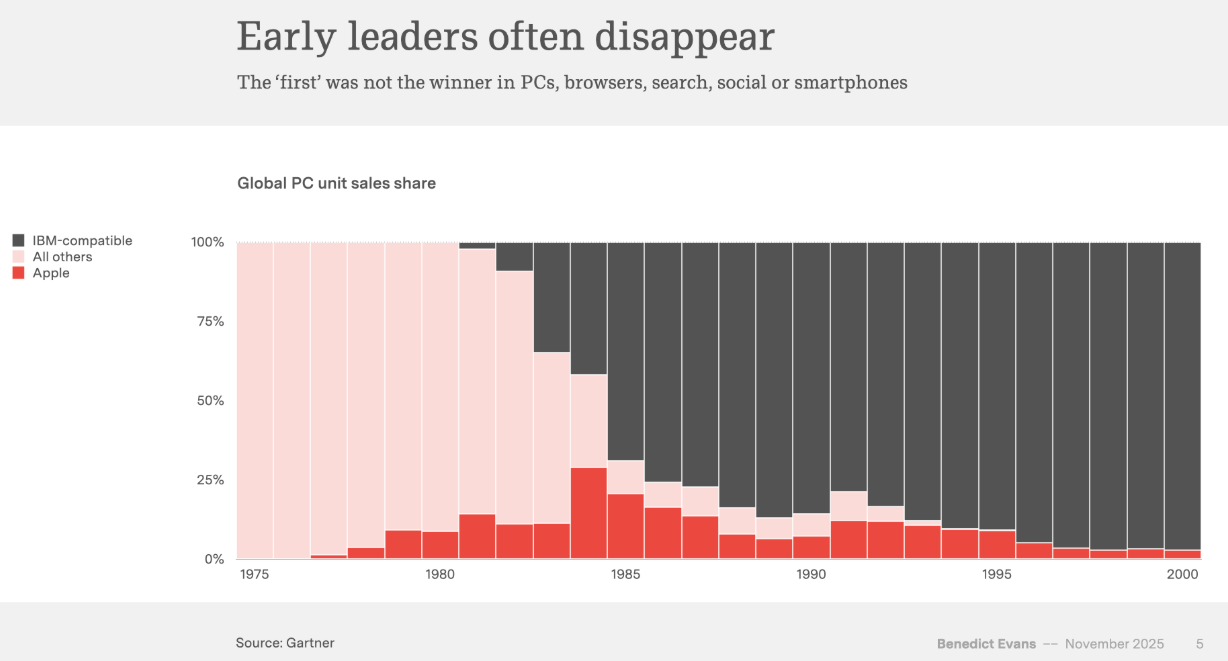

Early leaders often disappear

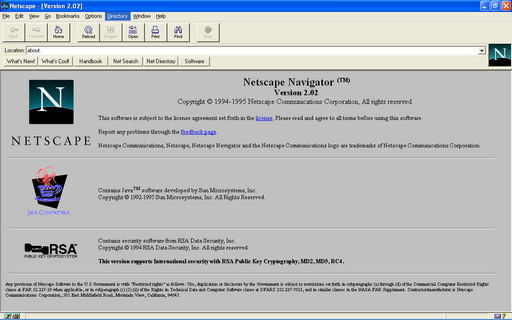

Going back a generation, there were a lot of people trying to make PCs before Apple and before IBM and Microsoft. And none of those companies succeeded. In fact, the same thing for web browsers, for search, for social, for smartphones. The first companies are very, very rarely the companies that end up getting all the value.

The current technology platform shift to Generative AI is similar to every other technological breakthrough. In the early days of car manufacturing, the auto industry was chaotic, experimental, and crowded with hopeful entrants. Between the 1890s and 1910s, hundreds of small manufacturers appeared in the United States and Europe, testing different technologies, designs, and business models. Most disappeared or were absorbed, but their collective experimentation paved the way for a few dominant players—like Ford—to emerge with scalable production, strong brands, and powerful distribution. It’s a familiar pattern: early leaders often vanish, value shifts to the new platform, and only a handful of companies turn a breakthrough technology into lasting economic power.

There is a lesson on innovation here - you have to have a lot of at-bats. You improve your odds of building something successful by having many attempts (experiments, prototypes, products, companies). Most will fail or be mediocre, but a few wins are enough to distribute the innovation to everyone else. Venture Capitalists use this to spread their bets across hundreds of start-up investments, knowing that only a few must succeed to cover the costs of hundreds of failures. Scientists and engineers understand the same thing: they have to keep trying as many times as it takes, in as many different approaches as it takes, to solve the problem at hand. This is why over-regulation is so dangerous - it prevents innovators from solving problems in new ways, forces entire populations into one solution, and makes people reliant on the government instead of themselves.

You improve your odds of building something successful by having many attempts.

It is one thing to create a technological breakthrough; it is entirely different to monetize it. That is why successful start-ups usually have multiple founders: a marketing/product person and an engineer, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak at Apple, Paul Allen, followed by Steve Ballmer (although not a founder) and Bill Gates at Microsoft, Marc Benioff and Parker Harris at Salesforce, Jimmy Wales and Larry Sanger at Wikipedia, etc. It is extremely rare to find a person who is both technically and marketing-savvy, like Thomas Edison and Elon Musk, who helped them attract the best talent to help bring their vision to life.

It is one thing to create a technological breakthrough; it is entirely different to monetize it.

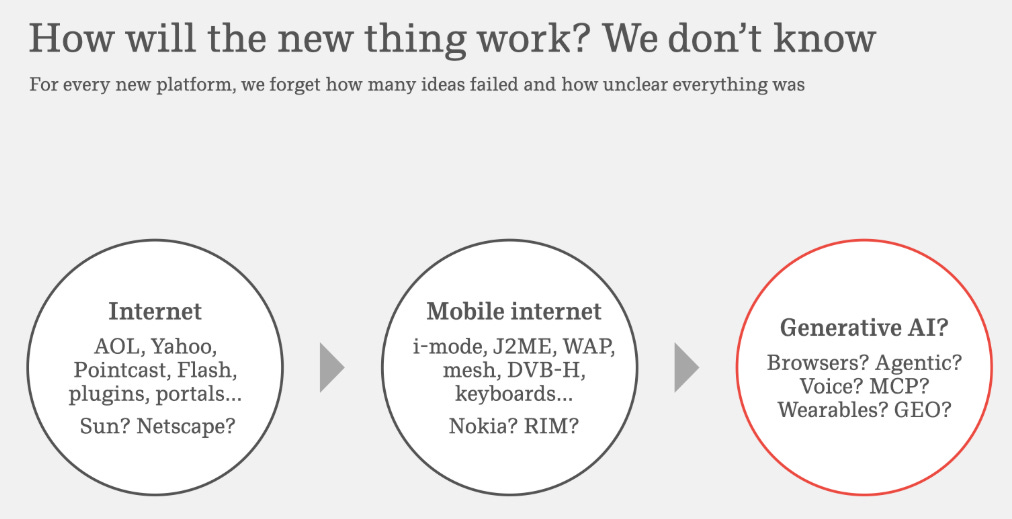

Most things will fail

We all use the web now, but it was not clear in the mid ‘90s how this was going to work. And there were all sorts of other companies and acronyms and ideas and business models that ended up not being the thing. The same thing for mobile. I used to come to Helsinki to talk to a company called Nokia. Some of you may remember it. And talk about IM mode and Java and WAP and none of those things were the future. The same thing with Generative AI now. We should presume that half the stuff we’re working on is not going to be the answer and isn’t going to work.

The reason so many start-ups and early adopters of technologies fail is that we don’t know how the new thing will work or where the value will be captured. The early stages of a new technology are periods of testing. It takes a few years to get enough people onboarded onto the new technology platform, to see how people are using it, and to understand for what purpose. That takes time, and many use cases will not make practical sense.

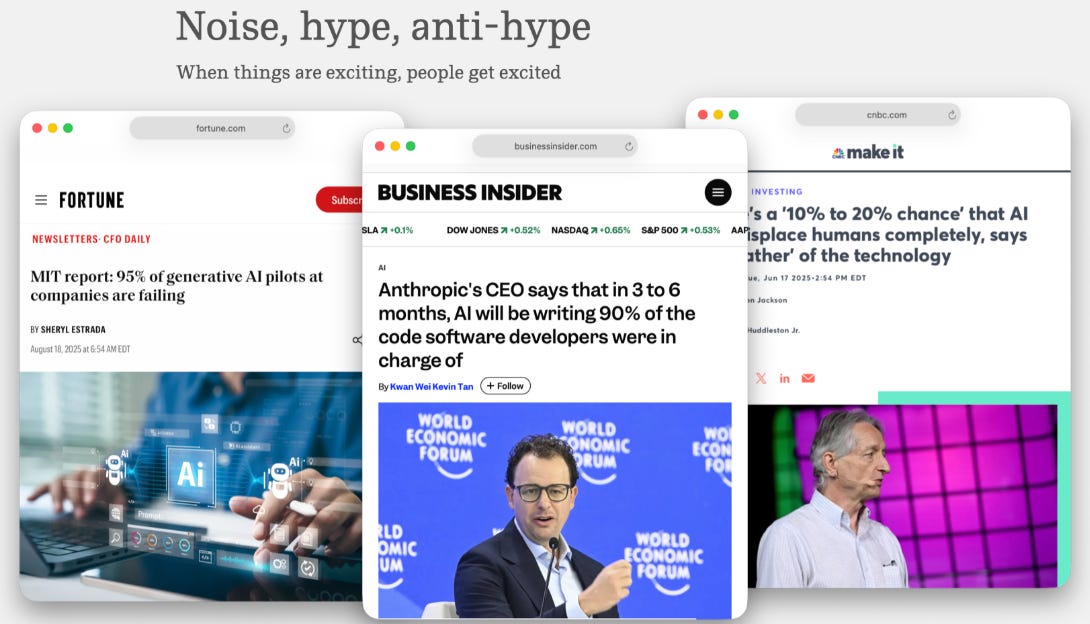

Hype and bubbles

… that means we get a lot of noise and a lot of hype and a lot of nonsense that you just kind of have to sweep aside and ignore.

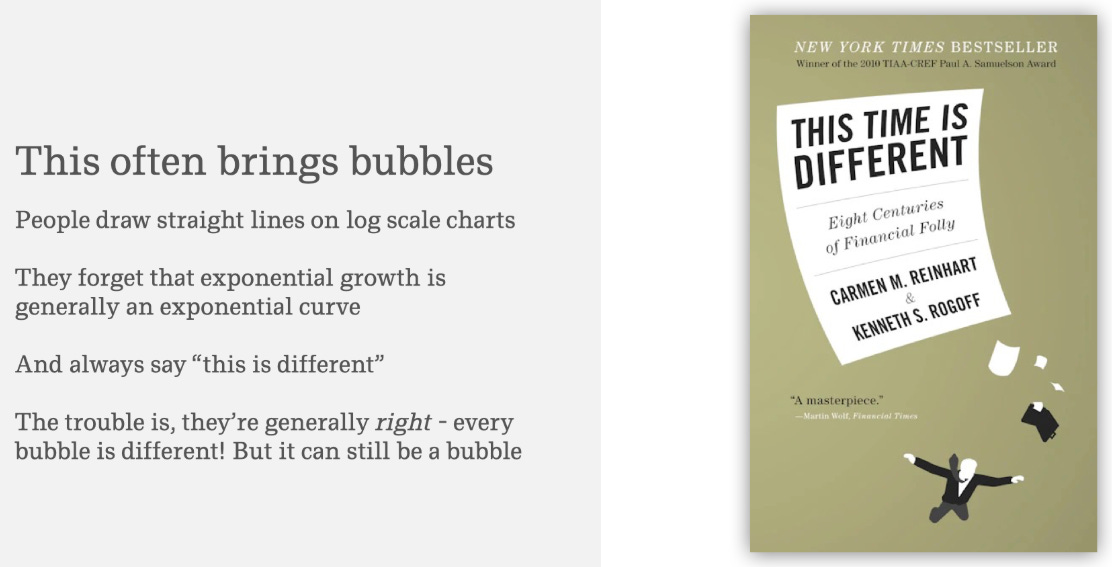

Trying new things means we don’t know exactly how it will work, which makes it extremely hard to get someone to give you money, whether to invest in it or buy it. So, to address the uncertainty that comes with new innovation, innovators have to overpromise and exaggerate what the thing will do for investors or buyers. This leads people to overinvest and overpurchase, creating asset bubbles.

You also generally get bubbles. In bubbles people draw straight lines on log scale charts and they say things like: “you just don’t understand how exponential growth works.” And they always say: “this is different,” and the problem is they’re always right. It always is different. The .com bubble was different. This is clearly different to the .com bubble. But it doesn’t mean it can’t be a bubble.

Naturally, when there is a lot of uncertainty, people throw everything at the wall and see what sticks. Through simple experimentation and iteration, people figure out how to use these new tools, what these tools are good at, and what they are bad at. But to even try, innovators need capital. How does someone get capital to test and try something new, unproven, and untested, without any guarantee that any of it will work? By promising and exaggerating what is possible.

Start-ups compete for capital like any other investment, whether it is real estate, a loan, a public or private company, or a piece of art. When investors can put money in an index fund and get 8% annually, or in Treasury bills and get a guaranteed 5%, you have to sell investors on a much larger return. After all, would you rather take 5% guaranteed, an 8% annual average over several years, or 2x or 5x your investment with zero guarantees? At what return would you give your hard-earned money to someone to do something that has never been done before? What would the entrepreneur need to try to achieve to make it worth losing your entire investment over?

To achieve such a significant return, a new technology must revolutionize, mesmerize, and cure all kinds of things, or at least promise to do so; otherwise, the risks of losing your savings do not justify the returns. This brings us to financial bubbles. Entrepreneurs promise a huge impact and hence huge returns to compensate for the risk investors take on. The potential for large returns attracts risk capital, which forces other entrepreneurs to overpromise and exaggerate what is possible as they compete with other innovators to attract investors. Why would you invest in a start-up B that promises a smaller impact with smaller returns instead of start-up A that promises a massive impact with huge returns?

Similarities with politics

This behavior is not much different from politics. Politicians cannot guarantee their solutions will work. What worked in one area at one time does not guarantee that it will work in another area at a different time. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Yet promises are free and don’t cost anything, so there’s no reason not to overpromise. You can always blame the consequences on a scapegoat: greed, billionaires, corporations, the other party, or the previous administration, to name a few.

Furthermore, new untested political ideas are no different than throwing things at the wall and seeing what sticks. The differences between trying new ideas outside of politics and implementing them through legislation are stark. If a political solution has negative consequences (which it always does, as every single action has a reaction that negatively impacts someone), it affects a much larger population, impacting everyone in the jurisdiction and many outside it, regardless of whether constituents agreed to it or not. Those who disagree have to live by the rules they didn’t want and their outcomes, and, what’s worse, they are legally unable to opt out unless they move to a different jurisdiction, which is hardly an ideal solution. This is often the cause of mass migration, as in Venezuela, where around 8 million people left the country because of its socialist government between 2014 and the mid‑2020s. Worst of all, it becomes punishable for others to try different solutions. Can you imagine being punished for trying a better solution?

In business, if you don’t deliver, people leave and take their business elsewhere. In politics, however, we are effectively stuck—either for the duration of the term or until the law is reversed. Reversals are rare and extremely difficult to pass, since legislators, no different from anyone else, including our early technology adopters, would rather focus on the new, shiny object. Take, for example, California’s Prop 47, passed in 2014 and not repealed since. It reclassified many non‑violent drug and property crimes, including some theft under $950, from felonies to misdemeanors, causing larceny theft rates to increase by 9%3, theft of motor vehicles to rise by ~25%,4 in some cases suspects calculated staying under the $950 threshold per incident; some cities (e.g., San Francisco, Los Angeles) have reported visible organized retail theft rings and “smash‑and‑grab” robberies. All of which led to hundreds of store closures and thousands of jobs lost.5 Who would have thought that lowering the consequences of stealing private property would lead people to choose theft over getting a job? With a single law, California pushed out honest job creators and innovators, lost thousands of jobs, made it harder to find a job, and made it more beneficial to steal. Worst of all, they are not in a hurry to fix it. Make it make sense.

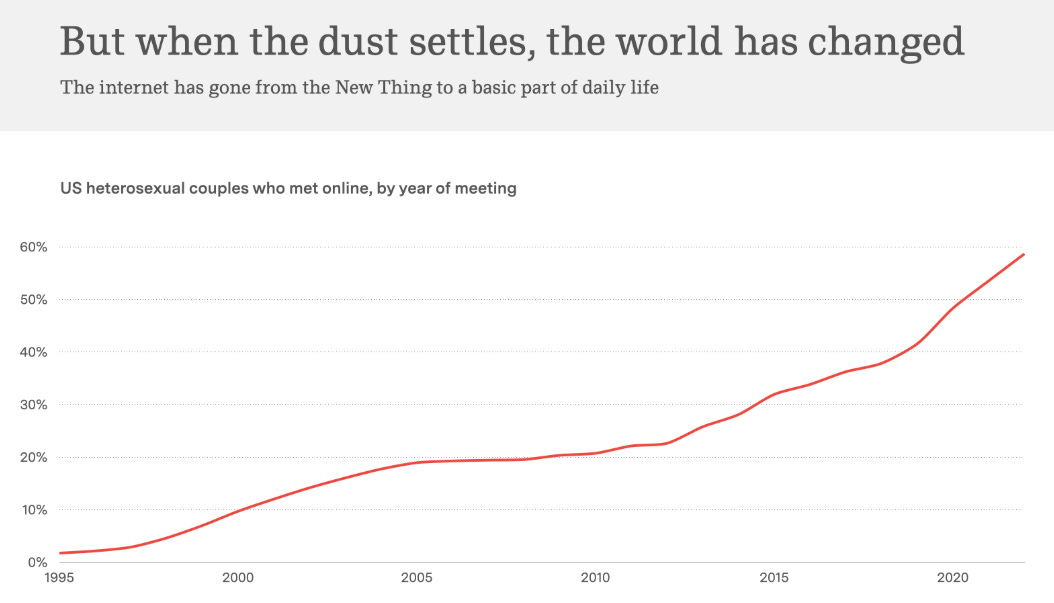

But when you sweep aside all the noise and all the dust is settled, the world has changed and it becomes part of the way we all live. Online dating now is about 60% of new relationships in the USA. This has just become part of the way the world works.

Although many innovations and their implementations don’t survive the landing, those that do change the way we live forever.

Explosion of new tools

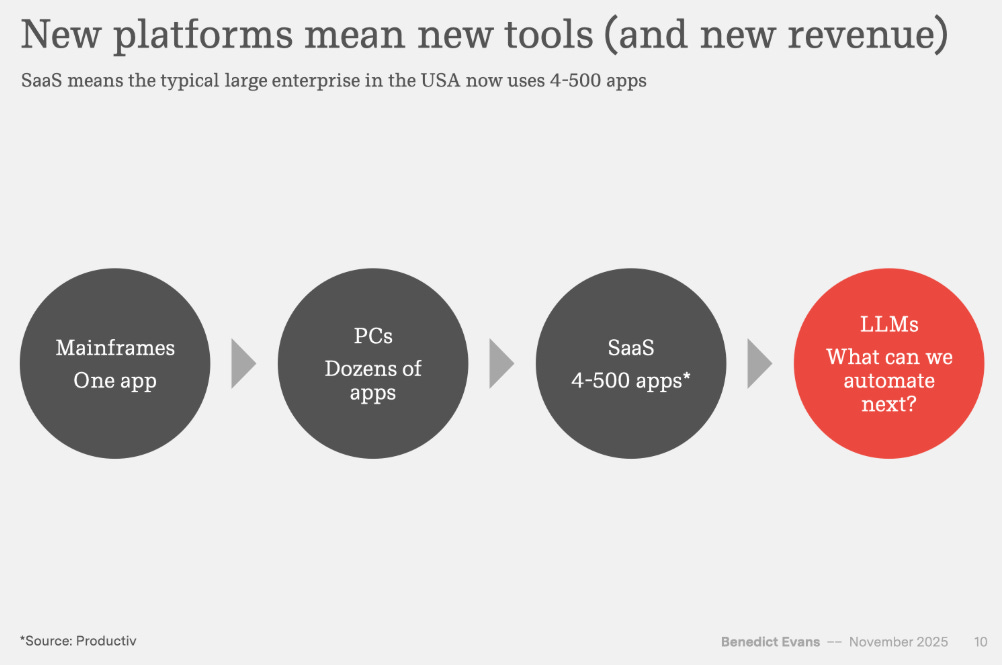

On the enterprise side, you get an order of magnitude more tools with each generation. When we went from PCs to SaaS (Web/Mobile), we went from dozens of apps to hundreds of apps. We automate more things with every step. We should expect the same thing to happen with LLMs.

Innovations, like LLMs, allow us to solve more problems by modifying innovations to our personal needs and creating tools specific to the issues we want to solve, thus creating an explosion of new tools and businesses.

Is this time different?

However, there is one way that this is all different from all those other platform shifts, which is with all the other ones, you knew what the physical limits were. You knew what the next phone could and couldn't do. You knew it couldn't fly. You knew that Telecomms wouldn't give everybody fiber next year in 1997. With AI, we don't know why these models work so well. So, we don't know how much better they're going to get. All we have is this sort of vibes based forecasting where people say what they feel might happen.

And so it might be that this is only as big as the internet or PCs or smartphones, which seems pretty big to me. Or it might be much bigger than that. It might be a much more fundamental shift. It's something more like electricity or computing or fire or like the next generation of humanity or something else. We just don't know. We'll have to come back in 10 years and find out.

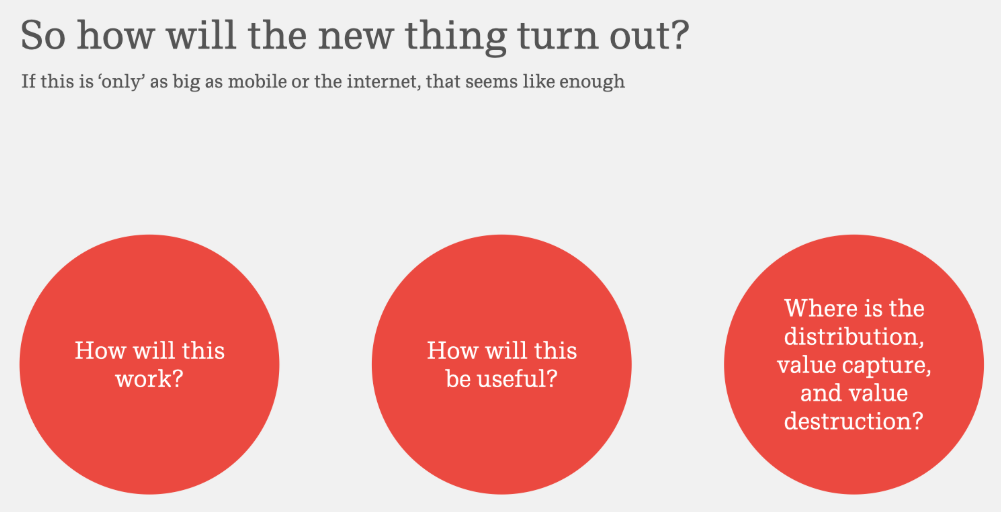

If this is only as big as the internet, that feels like enough to get excited about. And so we ask, well, how is this going to work? How is this new thing going to be useful? Where is the distribution and the value capture and the value destruction going to be as this thing gets rolled out?

Benedict poses several questions that everyone who is looking at this space, including investors, entrepreneurs, business owners, and users, is trying to solve:

How does it work? What can users do with it?

What problems and use cases does this solve? Ultimately, any technology is simply a tool used to solve problems. Some problems are more important, hence financially more beneficial, to solve than others.

What are the economics of it? How does it fit in the current ecosystem, and how does it impact everything around it?

I would also add: How does it work technologically? This is important to understand to get the full value out of it and innovate on top of it.

Technology is simply a tool used to solve problems.

Next lesson

In the following lesson, we will look at what has happened in the technology industry over the past few years in response to the latest technological shift.

Join our community

If you have business or investment ideas—or are looking for ideas and problems to work on—join us as we build a community of innovators and self-reliant problem solvers. Our goal is to launch a business and innovation accelerator that helps people who want to tackle problems around them turn their ideas into real-world solutions.

This post is public, so feel free to share it with anyone interested in AI or wanting to build something useful.

Thank you for reading! Please share your thoughts about the newsletter or problems you want to tackle.

Disclaimer

We reserve the right to change our minds about anything published in The Golden Age newsletter as new information comes to light.

Nothing produced under The Golden Age brand should be construed as investment advice. The contents of this publication are for educational and entertainment purposes only, and do not purport to be, and are not intended to be, financial, legal, accounting, tax, or investment advice. Investments or strategies that are discussed may not be suitable for you, do not take into account your particular investment objectives, financial situation, or needs, and are not intended to provide investment advice or recommendations appropriate for you. Before making any investment or trade, consider whether it is suitable for you and consider seeking advice from your own financial or investment adviser. This publication’s authors are not licensed investment professionals. Views expressed on The Golden Age are exclusively those of editors and not of any affiliated firm or organization. Do your own research before investing.

Ibid.